Top 10 Moments of Sondheim Genius

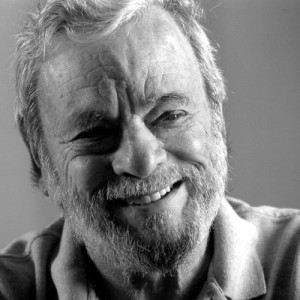

In honor of the eightieth birthday of the greatest musical theater writer/composer to ever live, I’ve gone ahead and curated the 10 most brilliant moments in a body of work that is chock full of genius. For purposes of this list, I’ve tried to identify specific moments, as opposed to stretches of time or entire songs. I’m not ranking the best Sondheim shows, or the best Sondheim songs, I’m identifying short bursts of time, rarely more than a few seconds, sometimes a single measure, when something remarkable happens. These are the moments to eagerly await each time a production shows up, the moments that reveal if the director and music director “get it”. And I’ve also tried to find moments that are not merely theatrical or musical, but moments when both the music and theater combine to make something amazing happen. Any one of his shows contains dozens of inspired musical gestures that bear close analysis, but these are the instants where the musical and theatrical ideas converge to a razor point of revelation, providing multidimensional insights into characters or situations.

In honor of the eightieth birthday of the greatest musical theater writer/composer to ever live, I’ve gone ahead and curated the 10 most brilliant moments in a body of work that is chock full of genius. For purposes of this list, I’ve tried to identify specific moments, as opposed to stretches of time or entire songs. I’m not ranking the best Sondheim shows, or the best Sondheim songs, I’m identifying short bursts of time, rarely more than a few seconds, sometimes a single measure, when something remarkable happens. These are the moments to eagerly await each time a production shows up, the moments that reveal if the director and music director “get it”. And I’ve also tried to find moments that are not merely theatrical or musical, but moments when both the music and theater combine to make something amazing happen. Any one of his shows contains dozens of inspired musical gestures that bear close analysis, but these are the instants where the musical and theatrical ideas converge to a razor point of revelation, providing multidimensional insights into characters or situations.

Today I’ll count down 10-6. Stay tuned for the top 5…

10 – A Musical Cross-fade (A Little Night Music)

The first act of the comedy of manners climaxes in this multilayered ensemble number as complex as the plots and schemes the characters are all concocting while trying to get into each other’s pants. Or petticoats. The first half of the number rapidly switches focus between several mini scenes as the players all consider their invitation to a Weekend in the Country. It’s a rare example of a musical number advancing the plot in less time than it would have taken to speak it.

The pious Henrick interrupts the proceedings with a broad majestic waltz where he justifies his participation in the ensuing hijinks by claiming “it might be instructive to observe”. (Not sure how that one would hold up in court.)

And here’s where the magic happens. Sondheim layers two competing time signatures to create the musical equivalent of a cinematic cross fade. Following a few spoken lines from our leading lady, the rest of the ensemble starts to enter with their own layers of themes and motifs. Their underlying meter is in four (subdivided into triplets), but Henrick’s grand waltz is still very present, and still in three, so the downbeats don’t line up, he’s very much out of sync with the rest of this lascivious bunch. It’s an exciting, bustling section, each character’s mini scenes intertwining, overlapping, in an uncertain meter, and building towards a unison statement of the chorus to end the act.

[audio:https://musicvstheater.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/WeekendInTheCountry.mp3|titles=WeekendInTheCountry]This is a tricky section to pull off and requires a musically accomplished ensemble. The polyrhythmic transition was abridged in the New York production and is marked as optional in the score. This recording of the National Theater Company production in London is the one of the few that has the transition section in its entirety. I only wish Henrik’s high G was a bit stronger. For a much more satisfying tenor G (although they use the abridged transition, visit the six minute mark here of the youtube clip of the Lincoln Center production)

9 – It Sounds Kinda Different When You Sing It… (Sweeney Todd)

Poor Mrs Lovett. She wears her maternal instincts on her meat stained sleeves. She wants, no, needs to have someone to take care of. But she is also a ruthless pragmatist, perfectly willing to eliminate anyone in the name of protecting her nuclear brood, even if this family consists of a revenge obsessed manic depressive and a half-witted emotionally deprived post-tween. So she’s in quite a bind when the two men in her life start veering towards a collision course. Poor Tobias believes that Sweeney is the sole source of wrongdoing in the Lovett pie shop and, full of vim and misguided chivalry, promises to protect his beloved caretaker from, well, anything bad that might be about.

[audio:https://musicvstheater.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/Not-While-Im-Around-Toby.mp3|titles=Not While I’m Around (Toby)]Mrs Lovett is placed in a position familiar to many single mothers, torn between the love of a child and the love of a lover, or what passes for a child and lover in this bleak cityscape. Tragically, Lovett stands by her man, but first she has to throw Tobias off the scent, and here Sondheim creates a lovely bit of musical imagery. Lovett echos Tobias’ refrain, “Nothin’s Gonna Harm You” right back to him, but it’s all wrong, a lone violin plays outside the key rendering Lovett’s comforting words anything but. Still, there’s a melancholy, mournful quality to the violin line. Lovett doesn’t want thing to be this way, but, alas, this is the world they’re living in.

[audio:https://musicvstheater.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/Not-While-Im-Around-Lovett.mp3|titles=Not While I’m Around (Lovett)]If Tobias was more sensitive to musical nuance, the story may have turned out quite differently.

8 – John Philip Sondheim (Assassins)

A great Sondheim device, a sarcastic sneer, a prickly condemnation that typifies the almost misanthropic nature of this remarkable piece. On its face, it’s a feel good all American story about every day people who manage to save FDR from assassination. But you don’t have to look too far beneath the surface to realize that, despite the many quotes from Sousa’s marches, Sondheim isn’t waving any flags here. For one thing, the singers are practically clawing over themselves for the chance to tell their story to the world, cutting each other off, desperate to trumpet their own dubious roles in the affair. And then you realize that their “heroic” actions consisted mostly of being selfish, rude, and inconsiderate; they wouldn’t let a shorter guy get close to the president, so when he pulled a gun he wasn’t able to get a good shot.

[audio:https://musicvstheater.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/FDR-Bystanders.mp3|titles=FDR – Bystanders]The whole time you see the small, almost pitiful assailant strapped to a chair, no parades, no cameras, just a miserable angry man with nothing to live for. He explains how he originally wanted to kill Hoover, but settled on Roosevelt since the weather was better in Miami, as an audience member you laugh, but hearing you, he suddenly turns straight to the audience. “No laugh! No funny!” And suddenly it’s not.

[audio:https://musicvstheater.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/FDR-Zangara.mp3|titles=FDR-Zangara]7 – Amorality Play (Into the Woods)

The first act of Into the Woods features three “discovery songs”, songs in which the characters reflect upon the challenges they’ve just overcome and how they’ve grown as a result. Little Red learns that guys act nice when they want something from you, Jack learns that there’s a larger world of powerful people in the sky and if you play your cards right, you can get stuff from them, and Cinderella learns the power of a well placed “maybe”.

What isn’t obvious to the casual listener is that each of these discovery songs are all transformations of the same underlying progressions and melodies. It many ways, they’re the same song, each transformed by the personality of the character that’s doing the discovering.

Little Red’s melodic theme (I Know Things Now) is simple, (mi) (fa) (so) (high do) (low do). It’s telling that this is actually a transformation of her “Mother said” motif (mi) (so) (la), like a distant memory that gets transformed squarely in Red’s home key when she actually incorporates her mother’s words. Children will listen…

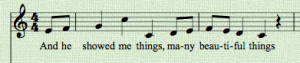

[audio:https://musicvstheater.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/I-Know-Things-Now.mp3|titles=I Know Things Now]And here’s the simple accompaniment. It’s just a fifth with an added ninth (no third?) and an inner voice moving up so-la-ti on the offbeats.

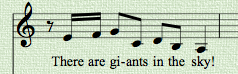

Jack’s theme (Giants In The Sky) starts out exactly the same as Little Red’s, but then has a few notes appended. These notes are derived from the Witches “Stay With Me” theme, which are also the same notes that Rapunzel sings incessantly. This is appropriate, Jack is singing about exploring the wide world just as the Witch is singing about keeping Rapunzel locked in a tower to protect her from that same world.

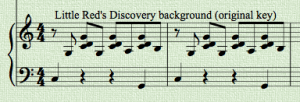

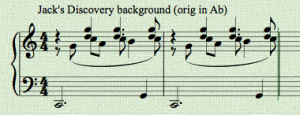

[audio:https://musicvstheater.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/Giants-In-The-Sky.mp3|titles=Giants In The Sky]The accompaniment is almost identical to Little Red’s background figure with the rhythm slightly altered.

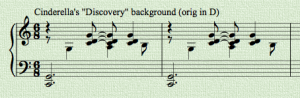

Cinderella’s theme (On the Steps of the Palace) is stated in 6/8 time, which harkens back to a hemiola figure that Cinderella sings early in the show with her sisters and her mothers grave. It’s appropriately more complex than Little Red’s statement, but the germ of the main discovery theme is there.

[audio:https://musicvstheater.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/Steps-Of-The-Palace.mp3|titles=Steps Of The Palace]The accompaniment again, arranges the same notes but shifted to 6/8. The same open fifth with added ninth, the same ascending so-la-ti line in the inner voice.

In the second act we find a different kind of discovery song, one that could only occur in the murky moral ambiguities of the deep woods. Rather than overcome an adversity or solve a problem, the Baker’s Wife has just committed a moral transgression, she has slept with Cinderella’s prince (or at least rolled around together on the forest floor). Ever a pragmatist (perhaps Mrs. Lovett is a distant descendant?) she uses her allotted discovery song to reconcile her actions with the morality that seems to come naturally to the rest of the “good guys”. Clearly the most intelligent character on this stage, she briefly touches on a wide array of subjects, musings on such adult topics as responsibility, sacrifice, compromise, and even a metaphysical digression on the discrete nature of experience “..if life were made of moments, then you’d never know you had one”. And then, beneath a blissful series of tonally ambiguous arpeggios, she paradoxically resolves to “let the moment go, don’t forget it for a moment though”, and then, using an exact restatement of the discovery motif as used by Little Red (“I know things now”) over a more syncopated version of the same background figure, she sings “just remembering you’ve had an “and” when you’re back to “or”, makes the “or” mean more than it did before.”

[audio:https://musicvstheater.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/Moments-In-The-Woods.mp3|titles=Moments In The Woods]This isn’t the bedtime story you tell your kids, its the story you tell yourself so you can sleep at night.

6 – Order From Chaos (Sunday)

My first exposure to most Sondheim works was via the original cast albums. One artifact of this is that I didn’t get to really experience the piece as a work of theater until local productions would occur or PBS would broadcast a performance from Lincoln Center. The thrill of discovery is somewhat lost, or at least diffused over several exposures, since the visual element comes long after the musical elements have already been heard and the synopsis read.

As a result, I can’t really fathom what it would have been like to witness the Act I finale of Sunday in the Park With George with fresh eyes. When would I have first realized that these seemingly unrelated clusters of characters were all taken from George Seurat’s masterwork Sunday Afternoon on the Isle of La Grande Jatte? Perhaps I would have caught onto it well before the end of the act, but I like to imagine the chills that would have occurred if I hadn’t seen it coming. Even knowing full well where we’re going, it’s a beautiful bit of theater, watching this taciturn and moody artiste compose the elements of his own experience into the image we’re all familiar with, making entire trees appear with a wave of his hand, tenderly granting his estranged lover a kind of immortality, a consolation prize, a substitute for the emotional availability he was unable to deliver.

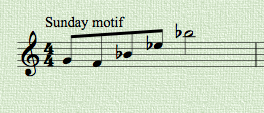

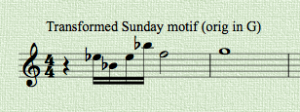

Already we have a powerful moment, but Sondheim goes one step further and creates a brilliant illustration of the significance of composition. The five note motif that begins the entire show:

Comes back transformed as the brass fanfare at the climax of this number:

They’re the exact same collection of pitches (transposed to a new key), but the effect is totally different. While the original statement is tonally ambiguous, a question mark, the second is clearly, irrefutably triumphantly tonal, outlining a major triad. The only difference is the order of the pitches, which causes different pitches to be emphasized. Thus the importance of the artist/composer, whose decisions create harmony and structure from chaos.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eVO9rN5Bk1A