24 Hours With Taylor Mac

A month ago I was testing my body’s limits, forcing myself to engage in Facebook debates even later than my customary 2:00 AM cut off. I was staying up until a bleary eyed 4:00 AM leaked into 5:00 AM, finally turning off the overhead light, and would be startled to find the room still illuminated by a disorienting, demoralizing haze of daylight seeping in through the curtained window.

I was training, preparing for an endurance test. I was about to attend Taylor Mac’s marathon performance spanning 24 Decades of American Popular Music in 24 hours. Non-stop. From noon on Saturday to noon on Sunday.

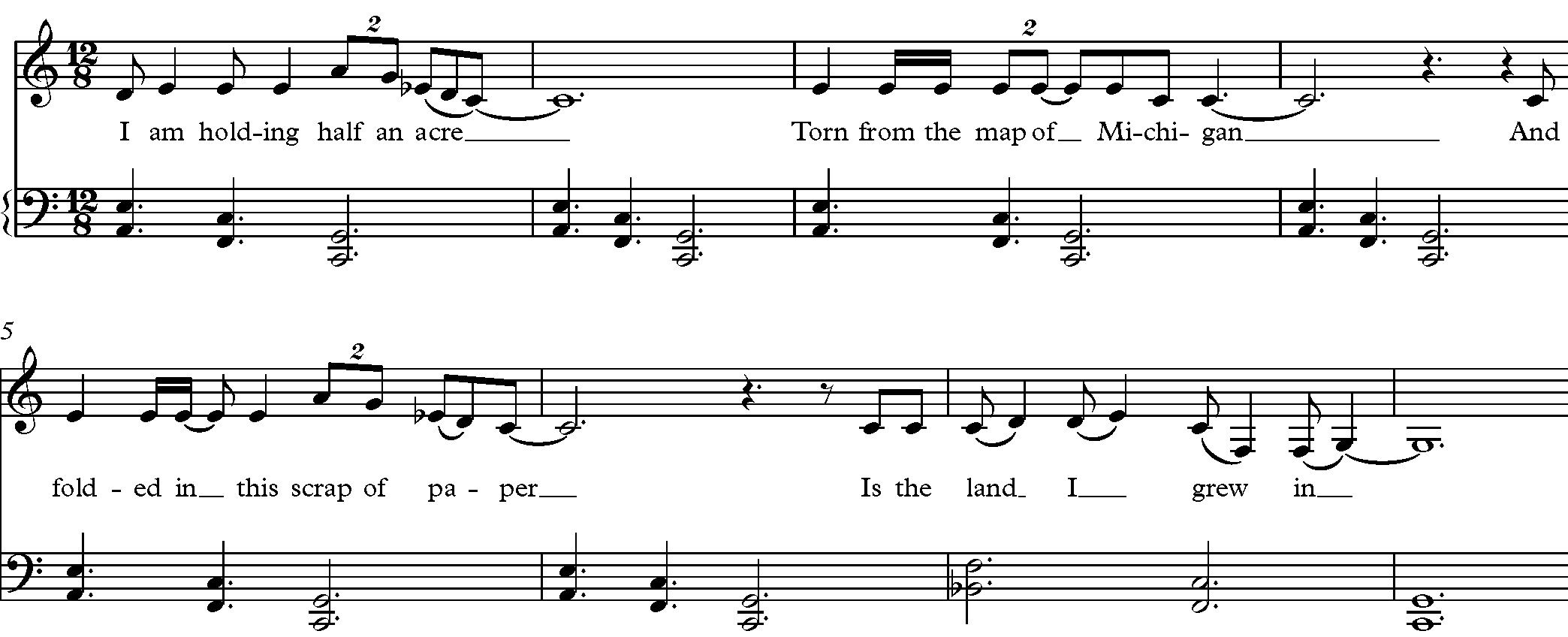

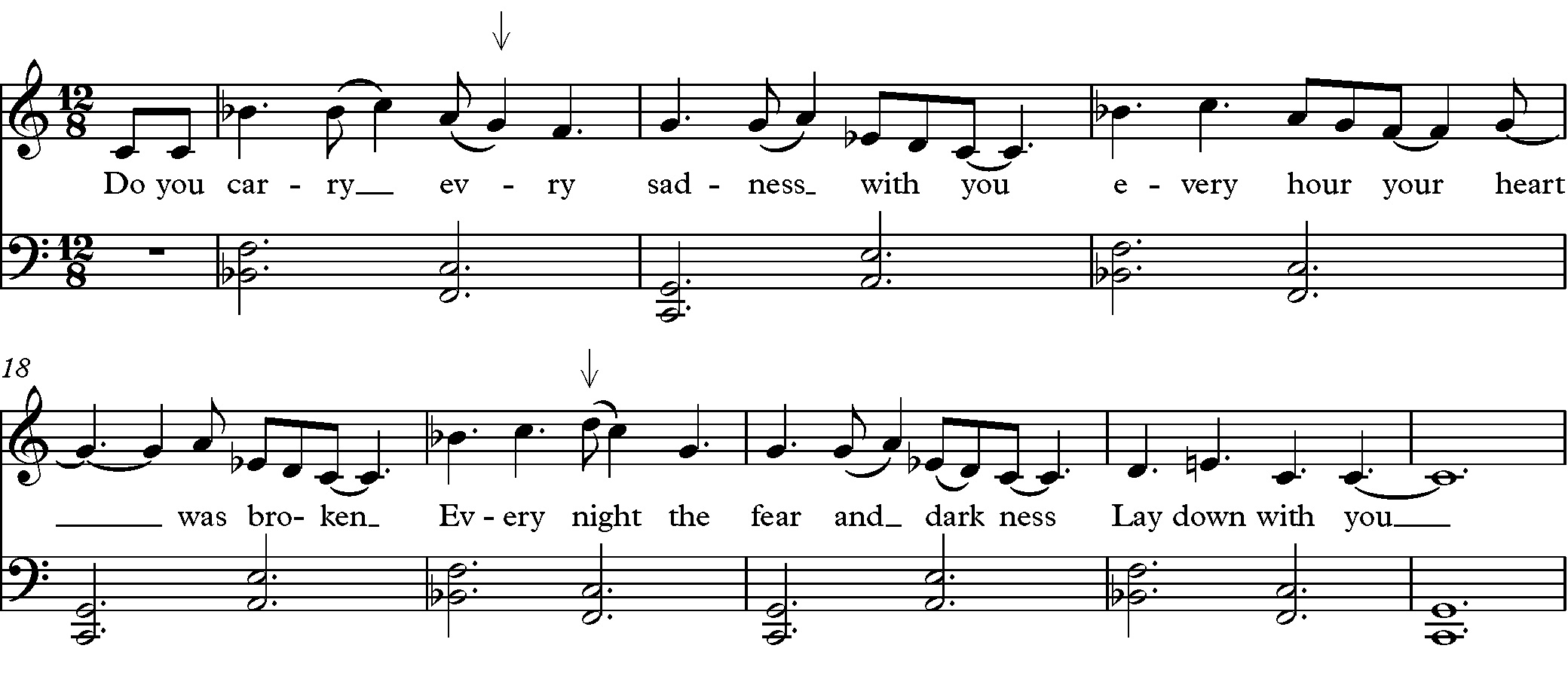

And not just as an audience member (as if anyone is truly “just” an audience member in Taylor’s brand of interactive participatory theater), but as a full fledged performer, a singer, one of a handful of vocalists from Choral Chameleon who would be playing the role of “prudish temperance choir that storms into a rollicking 1790s era pub and spoils everyone’s fun”. I was a collaborator. A colluder. I had crudite platter privileges in the green room.

I had already seen the first six hours of judy’s (Taylor’s preferred pronoun is judy, and I will be using it) marathon in San Francisco back in January, so when the co-producers at Pomegranate Arts reached out to the board of Choral Chameleon in July (which I sit on), it took about five minutes for me to chime in with my vote: a resounding “Yes, and I’m flying out for it!” I’ve been a fan since judy’s Lily’s Revenge took over a large chunk of Fort Mason and the Magic Theater with another sprawling multi-hour affair, there was no way I was going to miss an opportunity to be part of something this ambitiously insane.

24 hours. Each hour a different impractical and unwieldy costume. Each decade of America’s history contextualized and defined by the songs that were sung by its citizens. A multiply compound experiencing apparatus, America filtered through the minds of American songwriters, then subject to the market of American tastes and popularization, curated and reconstituted through the minds of Matthew Ray and Taylor Mac, and then collectively experienced again over a 24 hour period.

You know those little capsules you give kids? The ones that when you put them in water, the pill dissolves to reveal some foam dinosaur or something. In the days following the marathon, it felt like some very concentrated capsule had been shoved into my brain, one that would slowly transform into something else, a triceratops, or a spaceman, or Kentucky. Now, a month later, I still find moments from that epic day and night and day again occupying a new space in my brain.

In any given 24 hours in normal life, many many things happen. But most of them are largely automatic, habitual. I’d wager that under 4 hours a day are spent in actual engaged thought. So 24 hours of concentrated experience is something we are not built for. And this isn’t just experience, but intentional, surprising, entertaining, and provocative experience. So many things happened in that space of time last month. Simply listing my haphazard memories wouldn’t do the experience justice. But I have to do something.

So how about this: 24 Posts About 24 Moments in 24 Decades of American Popular Music in 24 Hours in 24 Days.

Huh. Ya know, I just thought of that. Right now. As I typed it.

That’s not bad.

Imma gonna do it.

Starting tomorrow!