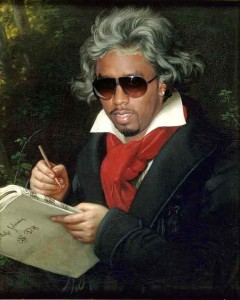

P. Diddy. Songwriter? Or Composer?

You heard me. P. Diddy. Songwriter? Or Composer?

You heard me. P. Diddy. Songwriter? Or Composer?

Perhaps I should back up…

After yesterday’s composition lesson with David Conte, he mentioned an upcoming radio interview with NY Times blogger and critic about town Chloe Veltman. (The interview will air next Friday, on her VoiceBox show on KALW). He thought that one of the topics would be the difference between composition and songwriting, and asked if I had any ideas to share.

My first thought was that songwriters have an inherently simpler task since they’re working within a well defined form. In song there is the expectation of a verse, refrain, chorus structure, some division of discrete chunks of material, and the songwriter “simply” (sic) needs to fill those well defined modules with appealing enough melodies, harmonies, hooks, and grooves. I’m hard pressed to think of any exceptions. On the other hand, music composition, especially in the modern era, has few if any expectations of form or structure. It is up to the composer to impose or realize a form appropriate to the material he or she imagines.

But the difference is less clear when you look at pieces in the classical era. Forms were still quite well defined, and while composers were remarkably inventive within those forms, there was some amount of connecting the dots and following prescribed structural practices. It wasn’t until Beethoven and the romantic era that form was subjected to the will of the composer in the name of their efforts to express the ineffable self.

Then what is the difference between composition and songwriting in the classical era? It doesn’t feel right to call Shumann or Schubert songwriters, even in context of their art songs. They didn’t just write those songs, they COMPOSED them.

David’s feeling was that pop songs, the product of songwriters, are less about the material and more about the expressive abilities of the performer. As evidence, he cited the dozens of covers of Beatle tunes in various styles, while there are no convincing reinterpretations or adaptations of Schubert songs or, arguably, classical pieces in general, Wendy Carlos and Emerson, Lake, and Palmer notwithstanding. (Actually, a college friend is writing a rock opera where all the songs are opera arias re-imagined as rock songs, so perhaps I’ll have to amend this argument.). A Schubert song is meticulously through composed, every note in the accompaniment and the voice is meaningful. You can’t change the notes, or alter chords or timbres without nullifying the end result. Pop songs, on the other hand, can survive any number of transformations, inflections, or outright re-harmonizations and still retain their essential character. There is something about the stuff of pop music, the melodic and harmonic choices that lends itself to such transformations.

This is another facet of the Definite vs Formless Content distinction. Pop songs are largely Formless while Schubert’s art songs are Definite. (Note that in this context, “Formless” means a very different thing than the structural forms of the classical era).

What about pop songs which are less dependent upon harmony and melody? Songs more reliant upon an arrangement of sounds and samples are not easily covered or transformed. Is it possible to cover a rap song, (other than ironically)? Do techno producers re-interpret the works of other techno producers to add their own personal expression of thumpa thumpa? If untransformability (ie Definite Content) is your metric, is it appropriate then to say that these untransformable works are more composed than written? Does this make P Diddy more of a composer than a songwriter?

So. Like I asked. P Diddy. Songwriter or Composer?

I’ll check in with David to see what he has to say…

> there are no convincing reinterpretations or adaptations of Schubert songs or, arguably, classical pieces in general

There are countless examples of cover versions of lower-case-c classical music: let’s start with Brahms’ “Variations On A Theme By Haydn” (although it has been suggested that the theme didn’t, in fact, originate with Haydn), Gounod’s adaptation of Bach’s Prelude in C, and any number of orchestrations and reductions. Then we move on to “A Lover’s Concerto” by The Toys, an adaptation of the minuet in G from the Anna Magdalena Bach book (sidebar: I once heard a ghastly Muzak version of this song — NOT its forebear, which is in 3/4 — in a Safeway); “Joy”, Apollo 100s revved-up version of Cantata 147; the Roto-Rooter Good-Time Christmas Band’s hilarious brass version of Sacre du Printemps; “Past, Present and Future” by the Shangri-Las; … There’s no end to it. Classical pieces can be reduced to melody and chord changes along with all but the most idiosyncratic pop tunes; there’s even a Classical Fake Book or two on the market.

And the most sublime pop music is no less reliant on specific arrangements than classical music is; comparing a cover version of, say, The Beatles’ “Yesterday” (of which there are many) with the original shows the differences. I would add that production technique is a third element in modern music of all genres; thus a cover of “Tomorrow Never Knows” or “Revolution No. 9” (or “Powasqaatsi” or a Nancarrow study) couldn’t possibly match the original exactly.

Such distinctions as “popular/classical” or “composition/songwriting” are convenient shorthands for marketers and critics, but evaporate under the mildest of scrutiny.

JR Brody! An honor to see the likes of you on my humble blog. Wondering how you came upon it…

You make a very good counter argument. While there is a distinction between music that can survive a distillation into “simply” changes and melody and music that needs to remain intact to retain its identity, there are examples of both in classical as well as pop music. The distinction between the two is, of course, a false one, but there still seems to a nugget of useful idea in the notion that some music is more wed to any particular realization than others.

To the point of the original post, I would still say that the person responsible for “Tomorrow Never Knows” and “Revolution No. 9” created them through a composition process as opposed to a songwriting process. But further thought might make me abandon the semantic construct and just get back to writing more music…